Nevada Appeal News Service

Glenn Downer is confined to a bed in his home and is now partially paralyzed after he was bitten by a mosquito and contracted West Nile virus.

BURKE WASSON

Nevada Appeal News Service

August 28, 2005

FALLON - While spending an August afternoon tending to his backyard garden, Fallon resident Glenn Downer was stricken with a common summertime nuisance - a mosquito bite.

But after a few weeks of deteriorating health and a few blood tests in September, doctors concluded the 83-year-old Downer was suffering from an affliction far from the ordinary - West Nile virus.

According to reports obtained from the Nevada State Health Laboratory in Reno and Quest Diagnostics in Las Vegas, Downer tested positive for West Nile in September 2004.

Since then, he has experienced multiple health problems including paralysis, blackouts and loss of memory and has been prescribed to a hospital bed in his home since Feb. 28.

While the West Nile virus is not contagious in humans and only mosquito bites can spread it, Glenn's 77-year-old wife, Doloris Downer, said she never expected something as small as that bite to cause so many health problems in her husband of 58 years.

"It's very serious," she said. "I think the fact that he was fairly healthy before he was bit makes it even more serious. But ever since then, he's just not the same."

Glenn is now confined to a bed in his home and is visited by various doctors and nurses' assistants a few times a week. While he struggles to carry on a conversation, he appears to be in good spirits and can acknowledge visitors.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, less than 1 percent of people who are infected with West Nile develop a fatal illness, and most don't develop any illness at all.

The fatality rate for humans who have been diagnosed with West Nile is 3 percent to 15 percent and is highest among the elderly.

The fact that Glenn was 82 when he was diagnosed with the virus in September and has lived nearly a year later has been tempered by the fact that he has experienced multiple health problems since his diagnosis.

After Glenn was bitten last August, Doloris said, he didn't show any symptoms or any illness for a few weeks until Labor Day morning.

"We were going to be out picking peaches and plums in the garden," Doloris said. "Glenn usually gets up and shaves and gets dressed right away. Well, that morning he was just slumped at the table and he said he was so tired. He said he'd never been that tired."

Doloris told Glenn to get some sleep, and he did - until 7 p.m.

Eventually, Glenn was taken Sept. 8 to Banner Churchill Community Hospital, where his memory slipped and he was suffering from the first stages of the virus, although no one yet suspected him of having West Nile.

He still experiences blackouts from his bed, and Doloris said Glenn told her he had "the worst one he ever had" nearly four weeks ago.

"His legs flew straight up and his eyes closed," she said. "He told me afterward he'd had quite a bad one."

Glenn is still on 72-hour pain patches for all the ailments he's contracted since being diagnosed with West Nile.

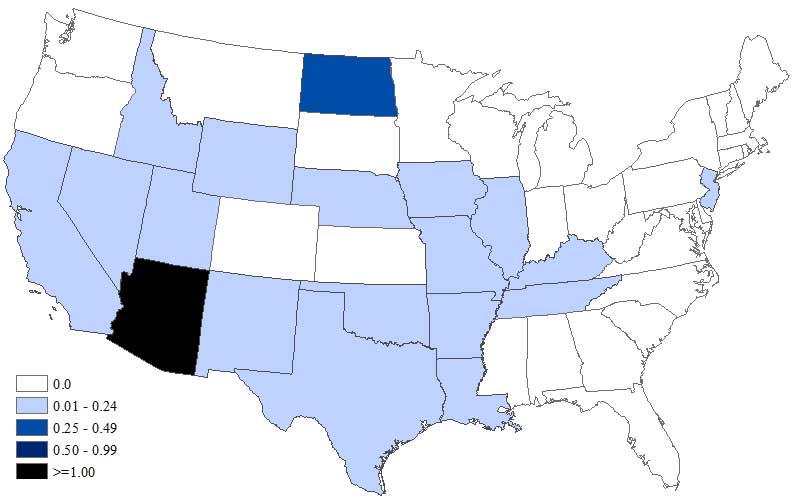

Through it all, Doloris said she never would have expected her husband to catch the virus, which made its first reported appearance in Nevada last year.

"I'm not sure what West Nile does to the body, but I know he's not been the same since," she said. "He's had a bladder infection, paralysis, spasms - he's just not the same."

n Burke Wasson can be contacted at bwasson@lahontanvalleynews.com