West Nile sickness wallops veteran

Fresno man was unaware of the severity of the virus.

By Cyndee Fontana / The Fresno Bee

(Updated Sunday, October 2, 2005, 9:51 AM)

Ron Orndoff hadn't missed a day of work in years and wasn't about to surrender that streak to a pair of wobbly legs.

Orndoff, 60, isn't the type of guy to crawl into bed for a cold or the flu. So when his 82-year-old mother suggested he call in sick on Aug. 14, Orndoff quickly dismissed the idea.

Instead, just as he did every other workday, Orndoff walked into the garage from their west-central Fresno home about 20 minutes before midnight. He headed toward their Toyota Camry and an eight-hour shift as night manager at the Quality Inn on Ashlan Avenue.

This time, the routine exit was followed by a loud thump.

The 6-foot-2, 230-pound Orndoff collapsed and didn't have the strength to drag himself to his feet. But as he crawled back into the house to call his boss, Orndoff was entering a harrowing medical drama.

Somehow — though he's not the outdoorsy type — Orndoff had been bitten by a mosquito carrying the West Nile virus. For the past six weeks, he has lived at Veterans Affairs Central California Health Care System hospital in Fresno while struggling to fight off high fever, partial paralysis, tremors and other symptoms related to the virus.

It was the hospital's first case of West Nile.

Orndoff developed meningitis and myelitis, an infection of the spinal cord, and his hands shook so badly that he couldn't lift a cup to his lips. Such severe symptoms are rare in most victims of West Nile, which attacks the central nervous system.

The majority of those infected develop no outward signs and only about one in five suffer flulike symptoms. Orndoff falls into the small category of people — less than 1% — who become seriously ill. People older than 50 and those with weakened immune systems are at greatest risk.

Neither Orndoff nor his family realized there was such a debilitating middle ground with the virus, which mainly makes headlines when it kills.

"Anybody I told about this, they had no idea that there's this serious effect," says Maureen Abston, Orndoff's sister. "We thought either you get sick [briefly] and recover, or you die."

Orndoff now is working to regain his health. His hands have stopped shaking and the high fevers have passed. He estimates that he's lost about 30 pounds.

He has sensation in his legs but limited ability to move them. Daily sessions of physical therapy are helping build the strength he needs to move himself in and out of a wheelchair.

Doctors can't predict whether he will recover full use of his legs. Orndoff says emphatically: "My goal is to walk."

While Orndoff only now is understanding the severity of his ordeal, his mother and sister believe he was twice close to death. They say he was confused at times — likely from the fever — and doesn't remember the worst days.

Orndoff, whose genial nature masks a stubborn streak, barely recalls an insect bite that bothered him in late July. Because he spends little time outside — his attempt to grow tomatoes lasted all of a day — Orndoff doesn't know where he met up with a mosquito.

"If you think of anyone who wouldn't be bit by a mosquito, it would be him," Abston adds.

In early August, according to his mother, Orndoff seemed to be suffering from the flu. But he'd managed to stay on his feet until Aug. 14, when he collapsed just outside the home he shares with his mother, Opal.

Orndoff had moved from Los Angeles back to Fresno in the early 1990s to help his mom. The roles were reversed when she found him in the garage that night.

Orndoff, who spent several years in the Army and once traveled the Midwest as an actor, knew he needed to see a doctor. But he decided to wait until morning before heading to the VA hospital, crawling back to his bedroom to sleep through the night.

The next morning, his mother drove the Camry over the curb and onto the lawn to shorten the walk for her weakened son.

"He crawled to the car," she says, "but he didn't have the strength to get in."

Opal Orndoff called paramedics, who ultimately transferred her son into the car. She drove to the hospital.

After a few hours, she says, doctors told her "we don't think he had a stroke but we don't know what it is."

Orndoff promised to call the next morning, and she finally left for the night. When he didn't call, she went back to the hospital and found "a room full of doctors" and a very sick son.

According to Dr. William Cahill, the chief of staff, doctors immediately suspected West Nile. He and other doctors have seen cases on the East Coast.

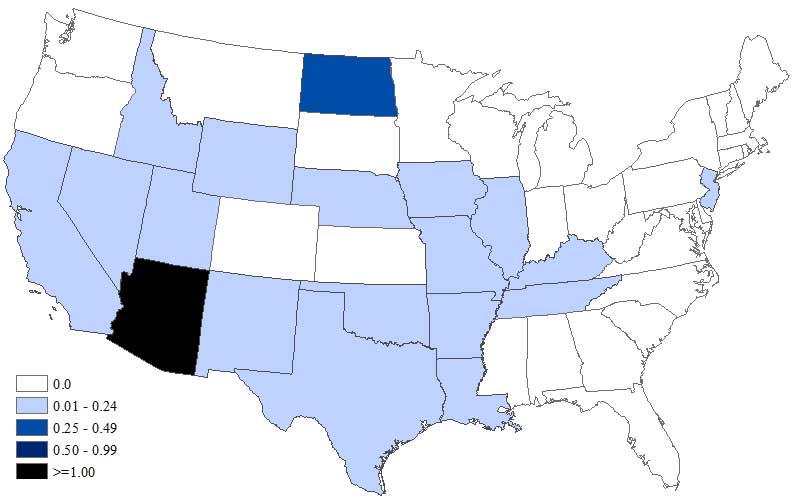

The virus first appeared there in 1999 and has since spread across the country. It can be transmitted to people or animals from mosquitoes that feed on infected birds.

In California this year, 16 people have died from West Nile-related illness. Six of the deaths occurred in Fresno, Kings and Tulare counties.

There is no specific therapy for the virus; doctors treat the symptoms that develop. In Orndoff's case, symptoms included a 103-degree fever and muscle weakness.

When doctors first tested Orndoff for West Nile, the results were negative. It was too early to detect it; a second test a few days later diagnosed the virus.

Dr. Hewitt F. Ryan Jr., a neurologist who treated Orndoff, says the initial negative test didn't affect treatment because "the pattern of his illness was so striking."

Cahill says it was important to diagnose West Nile to "confirm that we were on the right track, that we weren't missing something else."

Abston immediately drove to Fresno from Yuba City when word of her brother's condition traveled the family grapevine.

When she first saw her brother, he seemed heavily drugged, mentally confused and had little feeling in his legs.

Abston and her mother visited twice a day to help feed him lunch and dinner because Orndoff's hands shook so badly.

A blood clot complicated his recovery, and he spent several weeks in the hospital's intensive-care unit.

Now, he has recovered enough to move to the extended-care unit and begin physical therapy.

Chuck Toland, a physical therapy intern at the hospital, says Orndoff has improved dramatically since his first session. When the two started, Toland was handling about 75% of Orndoff's body weight.

Now Orndoff carries most of the load. On Thursday, Orndoff was deep into his physical therapy session when Toland asked whether he wanted to do more.

"It's up to you," Orndoff answered.

"I'm here all day," Toland said.

"Well, I'm here all day, too," Orndoff countered with a grin.

He remains upbeat while talking about his health. Orndoff says he doesn't fear dying and figures he'll go when his time comes.

He also doesn't ponder just how a man who doesn't spend much time outside wound up with West Nile virus.

"I don't know why it happened to me," Orndoff says. "I guess it's gotta happen to somebody."

The reporter can be reached at cfontana@fresnobee.com or (559) 441-6312.

No comments:

Post a Comment