CNEWS

Sun, July 24, 2005

Victim's W. Nile warning, Reality check for protesters on grave risks

By ROSS ROMANIUK, CITY HALL REPORTER

Before picking up an anti-fog placard, try suffering in my shoes.

That message comes from a Winnipeg woman who was once severely affected by the deadly mosquito-borne West Nile virus.

And she says protesters of the city's fogging operations are putting themselves and others at grave risk.

Genevie Cook contracted West Nile two years ago, becoming one of Manitoba's 35 serious human cases during a summer when the disease emerged as a serious threat in Canada.

"I was vomiting, shaking, I was weak and my hair was like straw," Cook, a 40-year-old health-care aide, told The Sun.

"I lost a lot of weight, I had a rash all over my body and a major headache. And I had no strength."

The symptoms sent Cook to Seven Oaks General Hospital in August 2003 for a week-long stay due to West Nile's neurological syndrome.

She was at the hospital "bodily," she says, "but in mind, no," while losing consciousness for long stretches.

"It was really scary. I was basically comatose. They didn't know what was wrong with me," Cook recalled.

"And when I was awake and alert, all I was doing was trembling. I was dizzy and nauseated. I had to take Gravol to even go for a car ride or just walk. I was so weak I had to have someone pretty much lift me off the couch or pull me so I could sit up."

Cook wants those protesting the city's use of malathion to understand how their disruptions could hurt the public far more than help.

Her warning is echoed by the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority.

"That's something I keep repeating -- that West Nile virus has to be given a great deal of respect," said WRHA medical officer Dr. Pierre Plourde.

Opponents of Winnipeg's skeeter spraying have long charged that malathion harms human immune systems.

The nerve agent comes with risks, Plourde says, but adds that it's safe at the city's low-volume fog levels.

'UNPREDICTABLE'

"The risk of malathion is minuscule," he explained. "So now you balance that against the risk of West Nile virus -- it's low, but it's increasing in our setting. It's unpredictable.

"We have a new virus that's only been around for a few years -- a new strain of the virus. It's mutated and it's become much more aggressive and lethal, potentially, than it was in Africa where it originated. And it's unpredictable. No one can tell you right now what we're going to see in the next few weeks. The worst-case scenario could be pretty bad, so one has to prepare for that."

Still occasionally suffering what she calls "the shakes," Cook says fogging opponents are "pretty naive" about mosquito season.

"They have to know what a person has to go through and feel -- when you lose your mobility and independence and have to build yourself up to start walking again," she said, noting she was off the job for about four months after entering the hospital.

Two Manitobans died from West Nile in 2003, while 142 people were infected.

Cook may have been among the lucky ones. Though only 20% of those who contract West Nile become ill, one of every 150 of that group might require hospital care.

Those victims have up to a 20% chance of dying.

"And your chance of being in chronic rehabilitation, of never being normal again, is upwards of 75%," Plourde said. "Only about one-quarter or so of those people who are hospitalized have full recovery, and can say they feel normal again."

News Clips and Information on West Nile Virus Survivors. Videos and links to News Articles on West Nile Virus Families, West Nile Deaths, West Nile Virus Prevention and West Nile Virus Symptoms

Sunday, July 24, 2005

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

CDC West Nile Virus Info

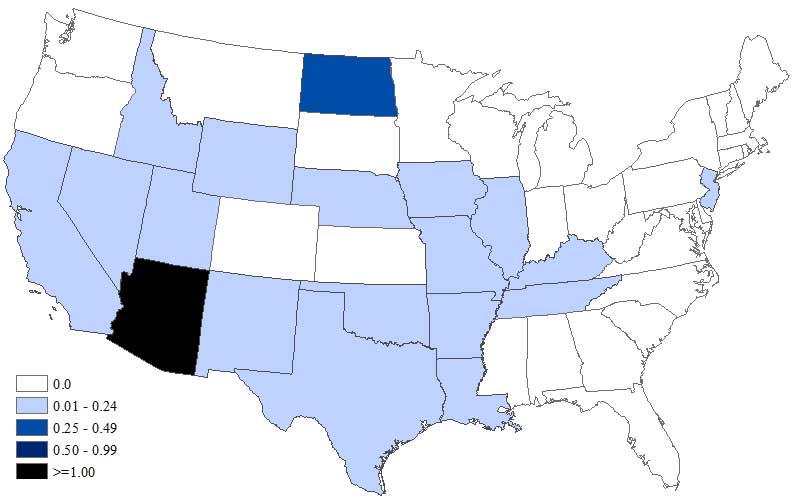

Skip directly to page options Skip directly to A-Z link West Nile Virus Neuroinvasive Disease Incidence by State 2019 West Nil...

-

Teenage girl in Menifee dies after four-year battle with West Nile illness Download story podcast 10:00 PM PST on Wednesday, December 10...

-

Skip directly to page options Skip directly to A-Z link West Nile Virus Neuroinvasive Disease Incidence by State 2019 West Nil...

-

Tosa man battling West Nile dies Steiner was principal of Wauwatosa West High School By KAWANZA NEWSON knewson@journalsentinel.com Posted: N...

No comments:

Post a Comment