Fighting West Nile's spread

BOUT WITH DISEASE SPURS SAN JOSE MAN

By John Woolfolk

Mercury News

Max del Hierro never saw the mosquito, and thought little of the itchy welt on his right ankle. But that bite in August was the start of a painful, crippling ordeal that nearly cost the San Jose computer engineer his life, and has since given him a new sense of purpose.

As the first and so far only person to contract the deadly West Nile fever in Santa Clara County, del Hierro has committed himself to helping people understand the threat posed by the mosquito-borne virus and the importance of fighting it.

``I'd really not like to see somebody else get as sick as I was,'' del Hierro, 51, said as he sipped a cup of black coffee one recent morning at the Coffee Cup, his favorite neighborhood cafe on McKee Road on the eastern edge of San Jose. ``I'm still recovering.''

Ten months after he was bitten, del Hierro is cheerful and high-spirited. But he still suffers numbness in the foot where the mosquito sucked his blood and injected him with the virus. He feels like he has lost his adrenaline. The mountain bike he loved to ride through the foothills near his home sits idle.

Del Hierro also suspects the virus may have contributed to his unemployment. The married father of three recently was laid off from the computer company where he had worked for 17 years, which was later sold. He wonders whether the dazed feeling he experienced during much of his recovery affected his job performance.

Del Hierro was well aware of West Nile virus before he contracted it. He knew that dead birds had been found infected with the virus in the hills where he liked to walk and bike. But it didn't occur to him that he might have caught the disease when he started feeling sick.

It was almost two weeks after he was bitten that he started feeling sick. It started on a Wednesday with stiffness and numbness in his legs, particularly the bitten limb. He was in pain, and had trouble walking. He soldiered through at work, where he was meeting some new bosses. By the time he got home Thursday, he was nauseated and feverish, and went to an urgent care clinic. He was told he had a routine virus and sent home.

Worsening illness

It was even worse the next morning. He had been up all night, twitching and tossing. He could barely get out of bed. Del Hierro checked in to an emergency room, but was sent home again. By that Sunday, Aug. 29, del Hierro was delirious with a 104-degree fever and taken by ambulance to Good Samaritan Hospital. He was so dehydrated, he recalled, that his skin seemed to sag off his bones.

Doctors pumped fluids into him, and gave him medicine to lower his fever and reduce his nausea. Del Hierro's field of vision narrowed; he said it was as if he was looking through a tunnel. Oddly, his eyesight temporarily sharpened to where he could see clearly without his glasses, something he suspects was caused by swelling in his head.

By Monday, del Hierro was fading in and out of consciousness and had resigned himself to the possibility that he might die. He was more dazed than afraid, and said he credits his strong faith in God with giving him courage to accept his fate.

Yet even as del Hierro lay in the hospital on the brink of death, no one was quite sure what ailed him. A frequent traveler, del Hierro had been to Malaysia, Los Angeles, Seattle and the Gold Country town of Angels Camp all in July, offering a host of possible sources of infection for his doctors to consider. They tested for malaria and yellow fever.

Del Hierro credits his family with pressing doctors to consider West Nile. His eldest son, a 28-year-old computer expert, ran his symptoms on the www.webmd.com Internet site. The symptoms were almost a perfect match -- all that was missing was a rash.

Del Hierro's wife of 30 years is a veterinarian, and his 24-year-old daughter is a physical therapist. He credits their medical knowledge, support of family and friends, his faith and the top-notch treatment he got at Good Samaritan with helping him pull through.

``Just imagine if I didn't have all these people around me,'' del Hierro said. ``I felt blessed and lucky.''

Illness confirmed

After four days in the hospital, he went home. A few days later, test results confirmed he had been stricken by West Nile virus, which has sickened more than 16,500 Americans and killed 656 since the first U.S. case was reported in 1999. This year's first human case was reported last week in Kansas. Ten stricken birds have been found this year in Santa Clara County.

Though his fever was gone and the swelling had subsided, del Hierro's ordeal wasn't over. He felt disoriented and had trouble walking.

Santa Clara County public health officer Dr. Marty Fenstersheib said del Hierro had an unusually severe case. Eight out of 10 people infected with West Nile virus develop no symptoms, and most of the rest experience only mild illness, he said. Only about one out of 150 infected people develop severe symptoms like del Hierro's, he said.

Del Hierro also had been reluctant to identify himself publicly as a West Nile survivor. Among other things, he worried neighbors would not appreciate having their street identified with the virus.

But eventually, he grew more troubled by what seemed to be a complete lack of public awareness about West Nile. Co-workers wouldn't shake his hand, apparently fearing they would catch it from him, even though it is only spread through the blood.

Even more careful

Careful about mosquitoes even before he got sick, del Hierro is even more so now. He dispenses encyclopedic knowledge of mosquito biology and the benefits and drawbacks of various repellents. His personal favorite is the Malibu Mosquito Inhibitor, a $15 lamp-like device that blocks the bugs' ability to home in on a person's scent.

Recently, after Santa Clara County vector control officials launched a campaign to raise homeowners' yearly assessment $8.36 to $13.44 for mosquito abatement, del Hierro was alarmed to hear friends and neighbors complain about the fee increase. To del Hierro, the cost -- a little less than 2 cents a day -- seems a small price to help fight something so dangerous.

``They're all upset about the 2 cents,'' del Hierro said. ``They don't understand.''

Del Hierro said near-death experiences like surviving West Nile changes people, a sense other survivors he has met over the Internet have shared. For del Hierro, it inspired him to take a more active role educating people about the disease.

On Tuesday, del Hierro spoke before a public hearing on the vector control assessment, urging fellow residents to support it.

``I think I've been given a chance to live again,'' del Hierro explained later. ``You see life totally differently. I've been given a chance to educate people. I feel strongly that people not get this virus. My getting sick was one too many.''

Contact John Woolfolk at jwoolfolk@mercurynews.com or (408) 278-3410.

News Clips and Information on West Nile Virus Survivors. Videos and links to News Articles on West Nile Virus Families, West Nile Deaths, West Nile Virus Prevention and West Nile Virus Symptoms

Wednesday, July 27, 2005

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

CDC West Nile Virus Info

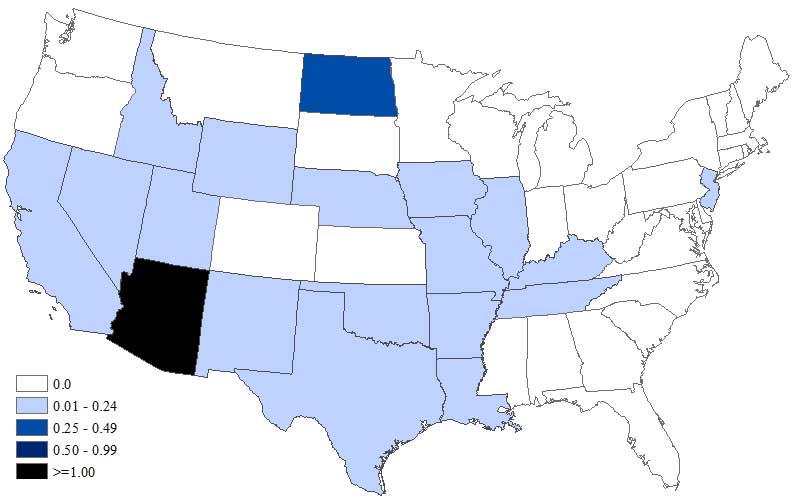

Skip directly to page options Skip directly to A-Z link West Nile Virus Neuroinvasive Disease Incidence by State 2019 West Nil...

-

Teenage girl in Menifee dies after four-year battle with West Nile illness Download story podcast 10:00 PM PST on Wednesday, December 10...

-

Skip directly to page options Skip directly to A-Z link West Nile Virus Neuroinvasive Disease Incidence by State 2019 West Nil...

-

Tosa man battling West Nile dies Steiner was principal of Wauwatosa West High School By KAWANZA NEWSON knewson@journalsentinel.com Posted: N...

No comments:

Post a Comment